“God gave us our memories so that we might have roses in December. “

~ J.M. Barrie

I treasure my time with older men. When I was five or six years of age my family lived in a part of town, that not too long before, had been farmland. Across the lane was a field overrun with wild flowers, black berries, and wild rose. I remember the old house that stood there to be low slung with a porch like the Radley house, in Harper Lee’s “To Kill A Mocking Bird”. The old widower that lived in it kept mostly to himself and was rarely seen. Of course, this made for all sorts of childhood speculation, particularly around Halloween.

I don’t recall his name, but I do remember that he trapped in the woods and creek bottoms where I played. He tended his traps early in the morning, long before I returned from school, and occasionally I’d see him skinning a raccoon or a fox in his back yard. He’d sometimes nod as I passed and eventually we became friends. He never said much, but he taught me how to keep a knife sharp, skin an animal, and light a kitchen match with my thumbnail. I always enjoyed our time together, and felt a deep loss when he died. Afterwards, the brambles around the old place seemed to take over, and the house had all but disappeared in honeysuckle by the time we moved a few years later.

The new neighborhood was every little boy’s dream. It was on the edge of farm country, and I had woods to play in, meadows to fly kites, creeks to catch crawdads, and lakes to fish. At the end of our street lived an old man that was rumored to have served in the First World War. It was said that he’d suffered from shell shock and was deaf. The old man lived alone, and his speech had degraded to the point where he could barely speak. He was a master fisherman, however, and when he prepared for a day at the lake, he had no trouble communicating his glee. The ritual began in his garden. When he determined the right place, he’d thrust his pitchfork into the ground and start strumming it. Within minutes worms would writhe on the ground for yards all around. He’d grunt and giggle at the bounty of bait at his feet. When he was sufficiently armed with a can of plump night crawlers, he’d pile all of his gear into an old wheelbarrow and set off for the lakes making a low humming noise. In the evening he’d return with a wheelbarrow full of carp and the occasional catfish. We’d all gather around to watch him clean his catch while he laughed and made a particular clicking noise that I still associate with carp.

One spring day he died, and his family came to clean the house and put it up for sale. It never occurred to me that he had a family, and I remember wondering why they’d never gone fishing with him. He was a happy man; I never saw him otherwise, even with all of the troubles he must have seen.

My Grandfather cinched my affection for older men. John White was a man who valued children, and was always a true friend to them. Once, at a formal Easter brunch, I knocked over a glass of orange juice. My father dropped his head and my mother looked alarmed, as my Grandmother rose from her chair to scold me. I looked painfully at my Grandfather, who winked and bumped over his glass of wine.

“Oh my,” he gasped. “That’ll probably stain. Bob, would you go to the kitchen for some water. Mother, should we put baking soda on it?”

When I was ten or eleven, I learned a brand new word while watching the high-school baseball team at their practice.

“Do you #@%&ing believe it?” One said.

“#@%&in’ right!” Another answered.

It seemed to me that every sentence they spoke had a variation of this new word.

That night at dinner, I looked across the table at one of my sisters and politely asked her to please pass the #@%&ing potatoes.

My father, unaccustomed to such table manners, had me by the shirt and in the next room before my mother had taken her second gasp.

“What’d I say… what’d I say?” I squealed. “I don’t know what it means!”

My father, sensing the truth, lowered me to the floor and mumbled; “Your mother will talk to you about it.”

The very next day my mother read me a wonderful story about flowers, pollen, stamens, and all sorts of interesting things. Afterwards, she closed the book and looked at me expectantly. “Mom, what does #@%& mean?” I asked.

“Go on out and play,” she instructed. “And, don’t say it again.”

That night my Grandfather called the house and asked for me.

“If you’re not busy tomorrow,” he said, “I’ve got some work around the place that I need help with.”

As I recall, my mother dropped me off on her way to the grocery store, and we got right to work in his shop. After we were covered in sawdust and the shop smelled of fresh-cut pine, he announced a break. As we sat on his bench and sipped a special concoction of his, a mixture of seven-up and grape juice, he said, ” I hear you got in Dutch with your father last night.”

“Something I said at supper. Mom read me a book about flowers yesterday.”

“So… what’d you say?”

I told him, and then asked, “Grandpa… what’s it mean?”

“Well, you’ll figure out the plumbing part of it all by yourself,” he said with a chuckle. Then, he went on to tell me about trust, respect, and commitment. It wasn’t until I was much older, and he was gone, that I understood just how special my Grandfather was.

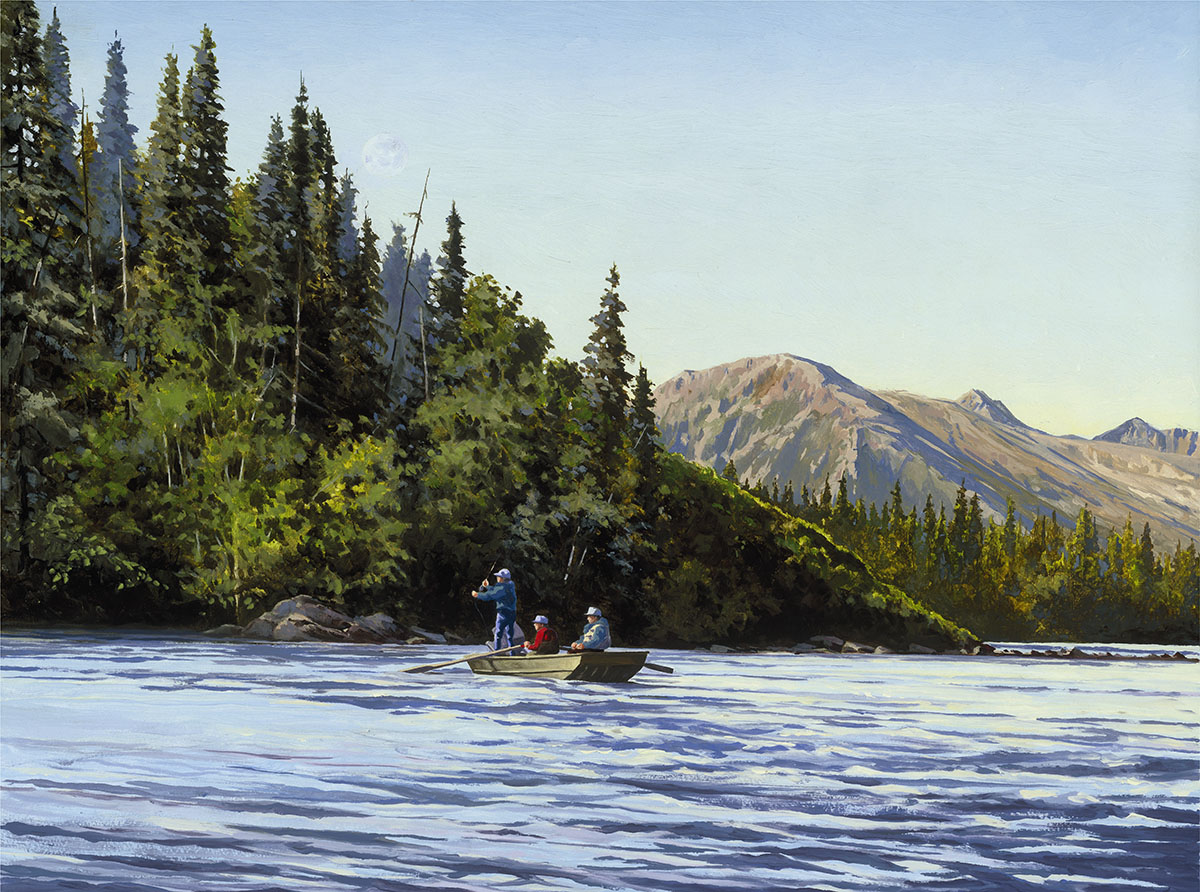

Years later, I found myself in Alaska, working as a fishing guide. One of my duties at the lodge was to plan the fishing schedule, and I rarely let an older fellow finish his week there without making the opportunity to spend time on the water with him.

It was the end of September and the end of another season. It also marked the end of my tenure as a fishing guide at the lodge, and I’d arranged to spend it with a friend and her father. My friend had fished at the lodge several times over the past few years, but I’d never met her father, who was a quiet and distinguished gentleman. He was a bit unsure on his feet, and although I know he didn’t want to, he fished while sitting most of the time.

Earlier in the week his daughter had let me know that he was dying.

“I guess we’re all dying,” I said, uncomfortably.

“This will probably be our last fishing trip together,” she continued. “And, this is how we want to remember our last day on the water.”

It was already a difficult time for me. I knew that I’d be leaving the lodge in just a few days; walking away from a place I loved. Over the past month, I’d found myself saying goodbye to a different river every day, with the knowledge that I might never see it again. But, as hard as it was for me, I realized that it was even more difficult for my friend and her father.

“Then, let’s make it a day to remember.” It was all I could think to say.

Our last trip together was a perfect autumn day. A late morning fog softened the long dark shadows that fell long across the water as we ran up river. The breeze chilled our noses and the sun warmed our backs, as the old man sat with his back to the wind and admired the day.

Few words were shared in the boat that morning; few were necessary. Each of us wanted desperately to hold on to the moment for our very different but similar reasons. Sometime after lunch, the old man struck a deep and powerful arctic char. Few fish are as beautiful as an autumn char, and as he held it in the water to revive it before its release, he asked me to take its photograph.

Few words were shared in the boat that morning; few were necessary. Each of us wanted desperately to hold on to the moment for our very different but similar reasons. Sometime after lunch, the old man struck a deep and powerful arctic char. Few fish are as beautiful as an autumn char, and as he held it in the water to revive it before its release, he asked me to take its photograph.

“Don’t you want to be in the shot?” I asked.

“Nah, just the fish… would you look at him?”

“Is he ready to go”? I asked, as I finished with the camera.

“One last look”, the old man replied. “Just one last look.”

The day ran its course as they all do, and soon it was time to return to the lodge. As we made our last drift, the old man, his daughter and I each studied the river valley, and framed it in our memories with one last look.