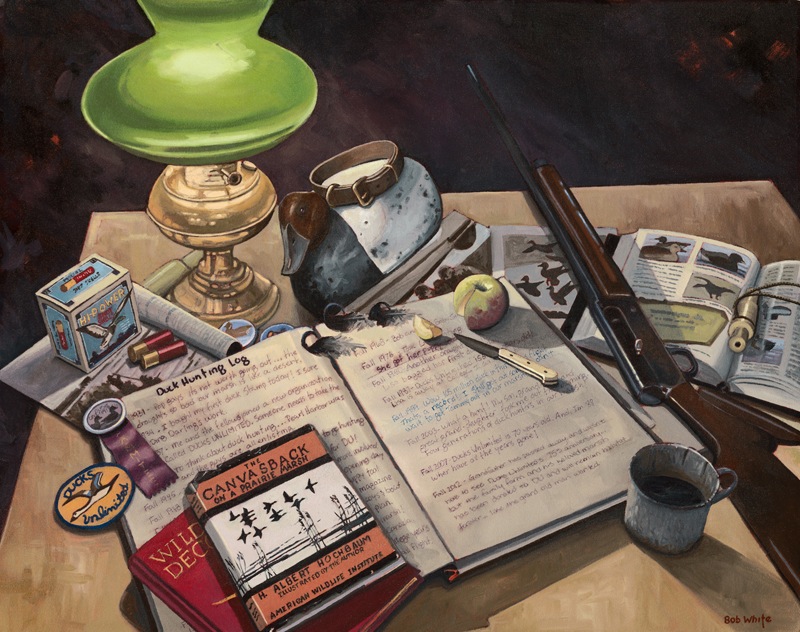

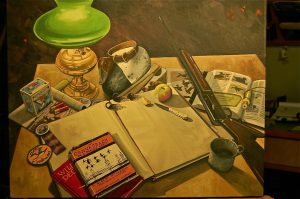

Painting for the Closing Column in Ducks Unlimited Magazine – Celebrating DU’s 75th Anniversary

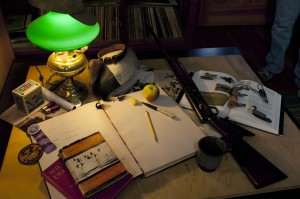

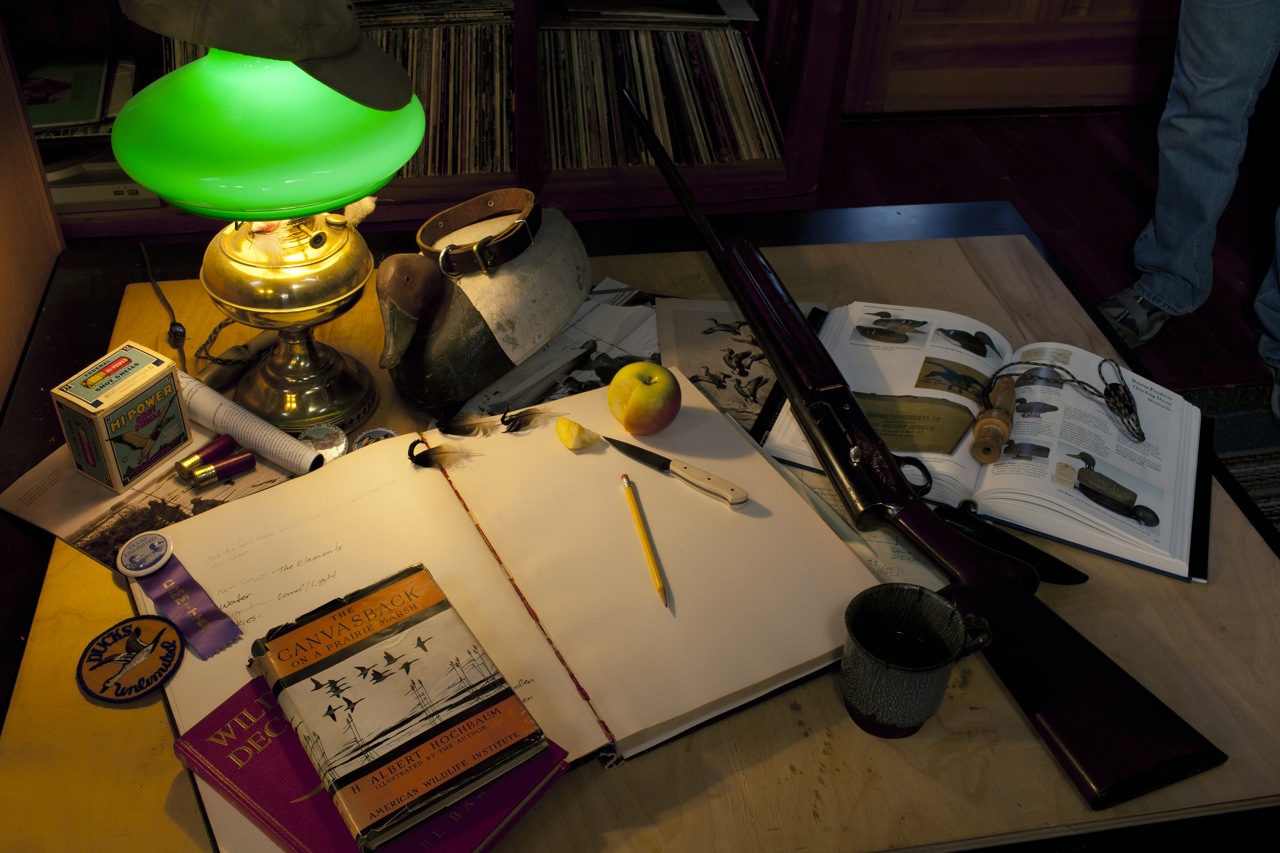

Step One – Setting up and photographing the still life.

Ducks Unlimited recently marked their 75th anniversary, and I was asked to compose a still life painting to celebrate the accomplishment. The painting would illustrate the closing column in the September/October issue of Ducks Unlimited magazine.

My friend and photographer, Mike Dvorak, stopped by the studio, one day last spring to help me set up and capture the image.

The image was to be a narrative – the history of a duck hunter, as told by the trappings on his desk. The central element of the composition is the old man’s hunting log.

Randomly placed around the log, under the dim light of his desk lamp is some of the memorabilia collected over a lifetime of duck hunting in a wetland on his family’s farm. This is where he grew up, and after he returned from WWII, raised his own family. It was on the same marsh that he introduced his son to duck hunting, and later his granddaughter, and eventually his great-granddaughter.

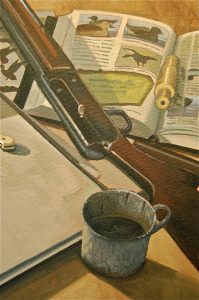

The items in the still life were all plucked from the corners and shelves in the studio where I paint and write. Dave Norling, noted Minnesota carver, made the canvasback decoy. His work can be found in the opened book on the far right, “Minnesota Duck Decoys”, written by Doug Lodermeier. My first duck call, which I still use today, weights the page. A flat-coat retriever’s collar rests atop the decoy. Beneath it, a photograph taken after a successful day of guiding, in an Alaskan salt marsh.

An old Browning A-5, which was made in Belgium, just months after World War II weights the right side of the composition. Every duck hunter has his favorite duck gun… and this is mine. It lies next to a favorite knife, given to me by a good friend.

The old Granite Wear cup was from my first river camp, in Alaska, in 1984. Had in not been hung upside-down in the spruce tree where I found it, I’m sure it would have rusted away decades before. As luck would have it, it’s been with me ever since, and has been known to see the occasional splash of Bourbon whiskey to celebrate the completion of a painting. It’s been a reoccurring prop in many of my still lifes.

I collect sporting books, and a large majority of them have to do with waterfowl and decoys. Two of my favorites rest on the hunting log, at the bottom left is “WIld Fowl Decoys”, by Joel Barber. It was the first in my collection of the old Derrydale Press, books, which have found themselves a home in the library. The other book, “The Canvasback on a Prairie Marsh”, was written and illustrated by, H. Albert Hochbaum, and was the impetus for me to write and illustrate my own work.

No duck hunter’s desk is complete with out an old box of paper-hulled shells. Perhaps, because it’s so colorful, one of my favorites is the old Federal Hi-Power box. The box and two shells rest upon a modern issue of Ducks Unlimited magazine. The page is turned to one of five paintings I did for a collection of essays about memorable hunting shacks, titled, “Great Escapes”. The painting-in-the-painting illustrates an essay by Jim Spencer titled, “The Poor Boy Duck Club”, in which he recalls hunting the Mississippi River Delta back in the 1960’s.

A few “weather feathers” and an assortment of DU badges and pins rounds out the composition and adds some color accents.

Next, in preparation for painting, the image is transferred to canvas.

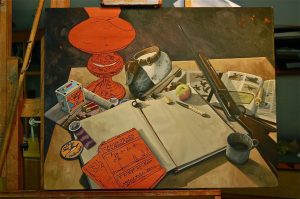

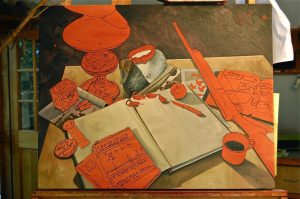

Step Two – The image is transferred onto stretched canvas and painting begins.

Step Two – The image is transferred onto stretched canvas and painting begins.

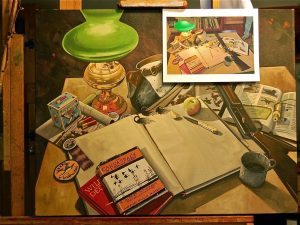

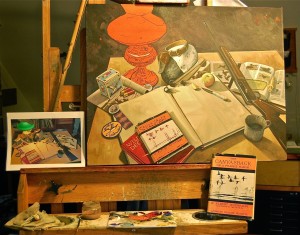

Since all the items in the still life are around me in the studio, I’ll paint from them, and a large print-out of the photograph.

A 30″ x 24″ inch canvas is stretched and prepared with an orange ground made by mixing alizarin crimson and yellow ochre. This is an old technique that I’d read about for years, but had never tried until Rick Harrington left me with a few of his prepared panels after visiting and painting at Bristol Bay Lodge a couple of summers ago. As I paint, small areas of the orange will be left to show through and produce a harmonic energy. This is particularly true when the areas next to it are of a complimentary color. The resulting shimmer will produce an added interest and vitality.

The image is then transferred to the canvas, drawn with a large black sharpie.

At this point I decided that the pencil on the old hunting log is an unnecessary distraction, and I remove it from the composition.

It’s time to put some paint on the canvas.

It’s time to put some paint on the canvas.

I begin by painting the two largest fields of color; the background and the desk top with the open log book. These are also the darkest and lightest values in the painting, excluding the lamp and some of the highlights it causes. This seems like a good place to start because it establishes both ends of the value scale and in doing so, I’ve covered a lot of the canvas.

Usually, my goal for the first day is to get paint on the entire canvas, roughly blocking in the entire composition, so that I can bring the painting along as a whole, giving it cohesion… but I don’t know if there’s enough time, given the complexity of the composition.

As it was, I had time enough to block in the decoy and some of the photographs and magazines on the desk.

As it was, I had time enough to block in the decoy and some of the photographs and magazines on the desk.

I had a bit of dark color left on my palette, and rather than scrape it off at the end of the day, I began to produce some of the shadows, which will fall across the horizontal planes of the composition. The last bit of black paint blocks in the coffee in my old tin cup.

Time to take a break from it, and see what the commotion is all about in the backyard!

More to come…

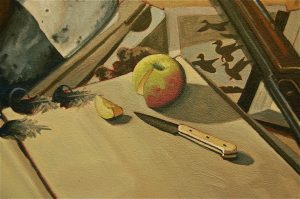

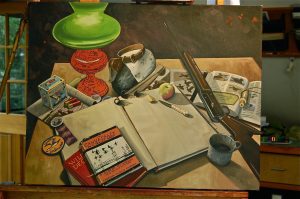

As I proceed, I find myself in a struggle between cognitive knowledge and my emotional needs. The academic prescription dictates that a painting be developed evenly; all parts progressing equally until the whole is achieved. My heart wants to see what the decoy will look like with Luke’s collar upon it. Will the old A-5 fall into the background, adding the sense of mystery I’m after? I’m excited to paint the apple!

No matter, there are many paths to the same end, and the painting won’t be completely finished until the last step, when the objects are enveloped in the warm glow of the lamp.

I’ve decided that the “rough-in” of the desktop is really quite nice in its looseness, and that I’d be wise to leave it as it is.

I feel an intuitive need to bring all the horizontal planes, the desk, books, photograph, print, and magazine to a point of near-completion. The trick with these planes is to give the viewer a strong enough suggestion as to what they are, without so much detail that they invite close inspection. To do so would cause confusion and not let the eye wander around the composition. I’m after the “suggestion of detail” without the clutter that too much of it can cause.

Additional work is done to bring the shadows forward. I find that the shadows are the important, unifying element in a still life painting… the cement that binds the individual objects to one another and the background; they are what give the objects depth and believability. They create a sense of place.

Additional work is done to bring the shadows forward. I find that the shadows are the important, unifying element in a still life painting… the cement that binds the individual objects to one another and the background; they are what give the objects depth and believability. They create a sense of place.

The grouping of “weather-feathers” proves to be a most difficult element to execute… dark soft edges that blend into shadows on a bright background. It’s hard to stay loose and suggestive.

The process of painting things that I spend a lot of time with is very interesting. When I know an object intimately, it will often seem to paint itself, as if some energy has taken over the process. When this occurs I find that the best thing I can do is to step back cerebrally, try not to think too much, and stay out of way. This was particularly true of the tin cup. It’s hard to say how many mornings I have warmed my hands and burned my lips on it… I believe some of that history is transferred to the painting because of it.

The process of painting things that I spend a lot of time with is very interesting. When I know an object intimately, it will often seem to paint itself, as if some energy has taken over the process. When this occurs I find that the best thing I can do is to step back cerebrally, try not to think too much, and stay out of way. This was particularly true of the tin cup. It’s hard to say how many mornings I have warmed my hands and burned my lips on it… I believe some of that history is transferred to the painting because of it.

More to come…

More Paint – the fourth session

More Paint – the fourth session

Just to be clear, a painting “session” is usually more than just an eight hour day… sometimes it’s several days, with time in between brush strokes to mow the lawn, weed the garden, work the honey bees, or play with the kids. I find that my “down time” is as important to the process as the time I spend working. The solution to one of a painting’s many puzzles is more likely to come to me while I’m working with the puppy in the backyard, as standing dumbfounded before the easel, with a dried out paint brush in my hand.

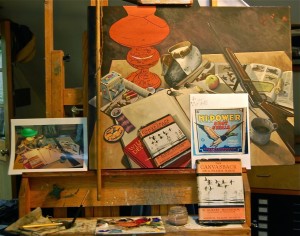

This fourth session found me tidying up small details; roughing-in the shot shell box, and the shells next to it. The apple and apple slice were a joy to paint, and afterward it occurred to me that, beside one other still life, I’ve not painted much fruit. How did I get past the bowl-of-fruit lesson in college? I must have cut class to go duck hunting!

While I avoid lettering text on the background objects, I feel compelled to hand letter those recognizable ones in the foreground; the shot shell box, the badges, buttons, and books. This requires a lot of time, and I’ll spend as much time on the shot shell box as I did in the entire first session.

In a perfect world, I’d leave the still life set up and paint directly from it, but space in the studio is limited and we have a puppy who spends his days with us… and he loves to chew on anything rare or expensive. So, at this point, I’ll settle with having the actual objects in front of me to augment the visual information in the photograph.

I’m at a point in the process where the light at the end of the tunnel is a small glimmer in the distance. This is when it becomes valuable for me to be able to lose myself in my work.

I’m at a point in the process where the light at the end of the tunnel is a small glimmer in the distance. This is when it becomes valuable for me to be able to lose myself in my work.

The shot shell box has provided me with some difficult decisions about how literal to be, or conversely, how painterly to remain. The sides of the box, which are in shadow, are the most demanding. Some detail is necessary, but too much of it will seem forced and heavy-handed. The large-scale scan of the box helps me decide what to paint literally, and what to leave suggestive.

Having the copy of Albert Hochbaum’s book, “The Canvasback On A Prairie Marsh”, at arm’s length is also extremely helpful.

It helps me strike the difficult balance between a perfectly lettered copy of the book, and a painterly rendition of it.

At this point I’m very happy with where the painting is at… and where it seems to be headed.

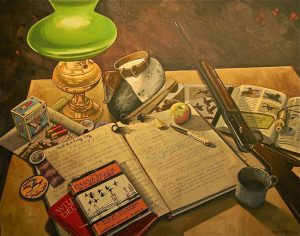

I’ve been saving the desk lamp, the orb and all that reflective brass for last.

It’s a bad habit of mine to leave what I perceive to be the most difficult part of a painting for the end. But… perhaps not. One might argue (in my defense) that all the time I’ve spent with the painting over the past two weeks has better prepared me to take on the painting’s biggest challenge.

Why am I so intimidated by the lamp? Perhaps, I feel overwhelmed because it is the soul of the painting… its primary source of light, and conversely – shadow. It is both luminescent and reflective.

Originally, I had intended to paint a ball cap draped over its top, as in the photograph. Upon consideration, and regardless of how much history I have with the cap (and at Lisa’s urging) I decided that it was too confusing, and should be eliminated.

I paint the globe, the all-powerful source of light.

I paint the globe, the all-powerful source of light.

I choose to use a very large brush to assuage my fears. Oddly enough, I feel that there’s not too much detail (damage) that can be done wielding a big brush… and, it seems to come together nicely. The color of the globe in the photograph seems to have a bit more blue in it, but in person, here in the studio, it seems warmer. Interesting. I’ll paint it as it looks.

It comes together.

I’m very happy with the open pages of the hunting log. It’s done in a very painterly manner, and seems accessible.

Other areas of the painting are brought forward based on the globe, and I add very small amounts of yellow and green into the highlights on leading edges and reflective surfaces of the other objects.

Next step… paint all that brass.

It’s time to tackle the beast… the highly reflective, often studied, but seldom-understood hunk of brass.

“It’s what you don’t paint, that’s most important,” a mentor once told me. “Look beyond what you think you know… and focus only on what you see.”

Not a bad way to look at life… and anyone attempting to paint a well-lit piece of brass or copper would do well to heed the suggestion as well.

I begin by troweling in a base color and add warmer highlights as needed, all the while desperately massaging and juggling shape, form, color and value. I find that it’s the dark passages that require courage. I add more Van Dyke Brown and plunge ahead.

In spite of my fears and shortcomings… things seem to come together. Magic is happening, and it seems to resonate throughout the rest of the painting. Passages that resolutely held their secrets now tell me what they need to be in concert with the rest of the painting. These moments of clarity, when all the parts of a painting communicate freely are exciting times for a painter. Information that was once coaxed, even begged for, is now given without reservation.

What time is it… almost dawn? No matter, I feel fine.

The lamp is finished the next day, and as it comes together, all the elements of the painting respond and ask for what they need to be in harmony with the whole. It’s incredible to feel everything come into balance with one another. It’s at this point that I begin to feel that the painting has a life separate from me… that it is its own being, independent of my wishes, efforts, fears, and shortcomings.

High lights are adjusted, up or down. Colors are altered, ever so slightly, to accommodate the last step towards completion. Little things are tweaked, and then suddenly, and without advanced knowledge or fanfare… the painting is finished.

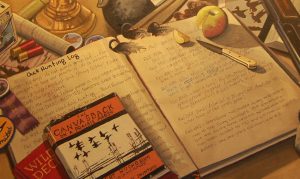

Well, except for the hand written notes in the hunting log. I have a fair idea of what this old duck hunter’s life was like, but I need to do some research on the Ducks Unlimited website to make sure my facts are historically correct.

I’ll do that tomorrow…

Content and Text for the Hunting Log

Content and Text for the Hunting Log

Just one thing remains to finish the painting, the lettering on the hunting log. To do this, I need to invent and document the life of the man whose imaginary desk I’ve just painted.

I had a good idea of what the old duck hunter’s life was like. Still, it took an entire day of research on the Ducks Unlimited website to assure that my record of his life matched the organization’s history.

The old fellow was born in 1921, and was ten years old in 1931, when the log begins. He lived through the Great Depression, a World War, and the creation of Ducks Unlimited, an organization he loved, shared with his family and friends, supported, and planned to support beyond his limited years.

In a nutshell, here is the life of the old duck hunter.

DUCK HUNTING LOG

– Fall 1931 – Dad says it’s not even worth going out… the drought is so bad that the marsh on our farm is like a desert.

– Fall 1934 – I bought my first duck stamp! I sure love Mr. Darling’s artwork!

– Fall 1936 – Things are bad for the ducks – the season has been cut to 30 days, but most of us don’t feel right about shooting any of them.

– Fall 1937 – Me, and the fellows have joined this new organization, DUCKS UNLIMITED. Someone needs to take the lead and save our waterfowl.

– Fall 1938 – Canada is involved in Ducks Unlimited too!

– Winter 1941 – It’s hard to think about duck hunting… Pearl Harbor has been bombed, and we’re at war! Me, and the guys are all enlisting.

– Fall 1945 – Home at last! The fellows and I can’t wait to go hunting!

– Fall 1948 – The prairies are back… things are looking up, and I have a SON!

– Fall 1958 – I haven’t hunted for almost ten years. Now that Bob’s old enough, it’s time to get him started!

– Fall 1960 – Times are tough for the ducks. There’s a drought in Canada. Thank goodness for DU…

– Fall 1963 – I got my first copy of Ducks Unlimited magazine!

– Fall 1966 – Ducks Unlimited is almost 30 years old! I need to get more involved.

– Fall 1968 – Bob and his wife had a baby girl! I have a granddaughter named, Lisa. The best part is that she was born on the opening day of duck season!

– Fall 1976 – I took Lisa duck hunting for her first time today… the puppy enjoyed it too!

– Fall 1980 – Another drought in Canada… thank God the DU projects continue to hold water… they’ll save the day. Lisa bagged her first duck this season!

– Fall 1986 – The North American Waterfowl management Plan has been signed… at last!

– Fall 1987 – Ducks Unlimited is 50 years old! Lisa is away at college, but I still get out some. I miss my hunting buddy!

– Fall 1995 – There were almost 37 million breeding ducks were in last spring’s flight north. It’s going to be a great year… and I have a great-granddaughter, named Tommy!

– Fall 1999 – Wow… 105 million ducks in this fall’s flight… the best year ever! I still get out some. I can’t wait to get Tommy out on our marsh.

– Fall 2003 – What a hunt! My son, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter took me out this morning. Four generations of duck hunters in our family marsh!

– Fall 2007 – Ducks Unlimited is 70 years old! And, I’m 88… where have all the years gone?

Next… the hand lettering begins.

With so much time invested in the painting, it’s a bit unnerving to begin the process of lettering on the blank pages of the open hunting log.

It became apparent to me, as I sized things up, that not every aspect of this man’s very full life would fit onto two meager pages of even a very large hunting log… especially with much of it hidden beneath other objects.

I decided to start at the beginning and the end, and piece the middle in as best as I could.

Once it was decided how to proceed, the next step entailed the physics of hand lettering the log in such a way as to make it look normal and realistic. Lisa suggested that she write the final entry, so that it would be in a different, and feminine hand.

I measured how much space she might need and preceded with the entry before, and then wrote to the top of the page, trying the whole time to letter at the perspective of the page in the painting. At one point, I decided to change the color of the pen, from black to blue… something I thought would be natural, and the blue pen smeared because I’m left-handed.

My heart went to my throat… until I realized such a thing would be natural enough. After all, I often do the same thing. So, it’s been established that the old duck hunter was also left-handed!

Once I finished with the second page, I began at the top of the first, in 1931, when the old hunter was just ten-years old. I then proceeded down the page, trying to fit in as much of the old man’s life as I could.

When I was finished, Lisa took her hand at it, and added the last chapter.

“Fall 2012 – Grandfather has passed away, and wasn’t here to see Ducks Unlimited’s 75th Anniversary… but the family farm and his beloved marsh has been donated to DU and will remain habitat forever… like the grand old man wanted. ~ Tommy White”

I thought that I was done, until I walked in the studio the next morning…

The internal struggle – making things look right.

The internal struggle – making things look right.

The pages of the log looked too perfect for my liking, and in much the same way as lettering the other objects, invited the viewer to linger on the details instead of perceiving the whole.

There was little I could do about it at this point, I thought, and then remembered an old trick; I could age and slightly blur the text with a thin coat of varnish.

This was a very tense moment. Too much bleed, would require repainting the pages and rewriting text; a time consuming process that I was prepared to do, if needed, but one I would find a bit heart-breaking.

It worked! The varnish gave the painting a perfect patina, and the effect of authenticity.

The painting was finally finished. It’s time to pour a bit of Bourbon into the old tin cup and toast my imaginary friend’s life and accomplishments.

Thanks for joining me, and congratulations, Ducks Unlimited!

BobWhite