“There are many ghosts at the Boca.”

– Jorge Trucco

My first season in Argentina passed as quickly as a waking dream. As the golden days of March fell away, subtle hints of summer’s end became increasingly clear. The Arucaria trees grew heavy with their seed, and storms in the cordillera hid the volcano, Lanin, for days at time. Squadrons of bright, noisy parrots, driven down to the valleys by the weather, seemed out of place. When the clouds were finally ripped from the mountains, a fresh mantle of snow reached nearly to their base, and condors soared high over the peaks.

In the mornings, the low sun warmed my back, and my nose chilled as I stared into the shadows trying to find another good fish. At our streamside lunches sitting in the sun seemed like a good idea, and offers of hot coffee, or the mate gourd were no longer politely declined. Evening came sooner, and as the autumnal shadows lengthened, Venus hung low in the western sky. The red stag roared their challenges long into the night and the fireplace in the lodge was no longer ornamental.

The end of any fishing season always brings with it a bittersweet mix of emotions. There’s a deep sense of satisfaction and accomplishment that is balanced by the anticipation of the next season’s work, half a world away. And always, there’s a bit of sadness with the leaving.

As the season wound down, my only regret was that I hadn’t guided or fished at the Boca of the Chimehuin. Most of my fishermen that first season wouldn’t have enjoyed the Boca, because like every other “big fish” spot, it requires a lot of hard work with no guarantee. A guide measures his clients with a critical eye before he suggests such a place, and even a talented angler might not have the discipline necessary to fish hard all day for just one strike.

With the passing of autumn my hope faded, until my friend and mentor, Jorge Trucco, told me that a sports-writer and his friend would be visiting the next week, and that they hoped to fish the Boca. Much to my delight, he suggested that we guide them.

A few days later, Jorge and I sat together at a tiny table in the airport at Chapelco. We sipped small, strong coffees and excitedly planned the trip. It was cold inside the tiny stone building that served as the terminal. Our sole source of heat was the small fireplace and the coffee we drank. A bitter Puelche wind blew from the east and wood smoke trailed over runway as the jet touched down.

Jorge and I had been through the process of greeting our clients so many times before that it had become automatic. We both wagered guesses about which of the Americans crossing the tarmac, while desperately trying to keep their hats from being blown away, were our fishermen. Once their identities had been established with handshakes and introductions, a bit of small talk and offers of coffee followed. Jorge played his role as host perfectly and sat down with his customers to answer their questions while I identified the bags and loaded them into the truck. When this was done, a nod to Jorge through the door started us on our way toward the Boca.

As we entered the small village of Junin de los Andes, Jorge, in a moment of inspiration, took a right turn and wound his way along some back streets to the old Hosteria Chimehuin. I had started my first season with exactly the same tour, and I was anxious to relive it after having guided in the area for four months. “We’ll take you to the Boca next,” Jorge said, as we entered the dark hotel lobby. The smoke-stained walls were covered in old black and white photographs.

“To know the Chimehuin and the Boca, you must first understand its history,” he said, gesturing to the images. “That’s why I’ve brought you here; these are the people who make the Boca a legend.”

“When I was a young man, Bebe Anchorena and Prince Radziwill rented apartments in the Hosteria for the entire season. It was common to see them here with Jorge Donovan, Laddie Buchanan, and many other famous Argentine fishermen. Roderick Haig-Brown stayed here in the early years, and your Joe Brooks, Ted Williams, Billy Pate, Mel Krieger, and others were always around the place.”

As Jorge continued, I drifted away and moved across the room from one faded photograph to the next. After a season of learning the water, these ghostly images now had more meaning. I recognized the Manzano Pool in one frame. In the next, I recalled the story I’d heard about La Piedra del Viento. In another scene, a little girl proudly held Jorge Donavan’s fish at El Puente Negro. Florencia Donovan, was now a lovely young woman, and she and her husband, Sindo, had become friends.

Jorge’s voice seemed to fade away and I sensed the presence of spirits. I smelled pipe tobacco and wet wool, heard the soft mummer of conversations punctuated with laughter and the clinking of wine bottles on glasses. Ah… the Boca has been kind to you, Joe. You should write about it in your new book. Would you like some more tinto?

The big fish rose to my skating spider as if he was a youngster… who would have thought!

How was your fishing, my old friend? You fished, “Las Viudas”, this evening, no?

“And that’s how I lost my biggest fish!” Jorge exclaimed, and I was immediately snapped back to reality. He paused, shook his head and quivered slightly. “What a depression!”

I could see that the memory of losing that big fish still troubled him and that it always would.

For the next forty minutes, as we followed the Chimehuin upstream to its source at Lago Huechulafquen, Jorge drove in silence, painfully reliving the loss of his big fish. When we approached the middle of the bridge near the Boca, he brought the truck to a stop. Suspended there over the river, he slowly turned to us and said; “There are many ghosts at the Boca.”

We were in luck! Standing in their waders around a small warming fire, sharing mate, and their stories, were the legends of the Boca. “Hola, Trucco! How have you been?” Asked Bebe, hugging Jorge and switching to English for his American friends.

“Very good, Bebe, very good… and you?”

“Oh, I’m well enough, but the fish are better. Hoy, no molestado. Today, I’ve been a good boy; the fish are untouched! Who are your friends?” Bebe asked.

“You know Bob; Señor Roberto Blanco.” Jorge said, and Bebe laughed.

“Oh yes, I’ve heard all about him!”

“And these are my friends, Peter and Richard, from New York City.” Jorge continued.

“I’m very pleased to make your acquaintance,” Bebe said, shaking their hands. “Let me introduce you to some old friends of mine. This is Prince Charles Radziwill and Jorge Donovan.”

Introductions were made and the mate gourd passed around while we pulled on our waders and asked about the fishing. Reports had gotten back to Bebe that a number of big fish had dropped down into the river. They’d fished since dawn without success, and now warmed themselves, deciding whether to continue into the afternoon. “Aye no suerte.” Bebe announced. “Why don’t you fish and we’ll stay next to the fire, where it’s warm.”

Fishing at The Boca is a social event, and there are particular places where one stands to cast. A fisherman works the water in front of him methodically for 15 to 20 minutes and moves to the next position, relinquishing the spot to the next angler who follows. There are four or five such stations before the first big bend, called the “Fools’ Pool”. The lead position is one of respect, and the most senior fisherman in the group is usually asked to begin the procession. In this case, our clients were deemed most important, and they were asked to start.

Jorge read my mind as he watched my gaze drift from the river to my unopened rod case. “Why don’t you follow, Señor Blanco?” He offered. “There’s not much guiding to be done here today.

I’d waited for this opportunity the entire season, and my rod was strung up in record time. I tied on fresh tippet, while Jorge led the others to the water, and suggested that they use a large, dark fly.

Peter and Richard fished through the sequence twice, very quickly, before Jorge joined them for a third circuit. Jorge is a thoughtful fisherman, who knows the value of fishing such a place in a slow and methodical manner, and his two clients were finished long before he’d reached the second position. I suspected that he would give much to have another chance at the big fish he lost in 1976.

As a sign of respect, I waited until he was at the third position before I began. I tested the strength of my knots, and the sharpness of the hook, stripped line from my reel and took a deep breath. I began to false cast until my timing smoothed out, and made that first long cast. I felt then, like I feel now when I buy a lottery ticket; don’t tell me about the odds… I just KNOW this is the time I’ll hit it big.

The first cast hit the water and started to swing with the current as the sinking tip pulled the big, black, maribou muddler below the surface. I saw in my mind’s eye, what I had dreamt might happen, and tensed as the line straightened out at the end of the swing. As I stripped it back I felt exactly the same way as when my lottery ticket doesn’t win; the next one just HAS TO BE A WINNER!

I paced myself to my friend Jorge, cast as he did, and let the fly swing it’s entire arch before I started a retrieve. Soon, the rhythm of our casts was the same and neither of us watched the other. We were each lost, me in my dreams, and Jorge in his memories. We both fished through the stations without a touch, and Jorge wisely decided that it was more important to attend to his customers and catch up with his old friends than to chase ghosts. “You go ahead, Bob,” he said. “Fish it through again. These guys are all having a good time, and I’ll open some bottles of tinto.”

I walked back to the lake as Jorge went to the truck for wine. Someone added wood to the fire and a shower of sparks towered into the darkening sky and drifted off, disappearing before the east wind.

By the time I’d reached the second station, I’d become mesmerized by the sound of the waves, the wind, and the repetitiveness of the casting. I was thinking about ghosts and what Jorge had said when it happened. The line came tight and my rod bent double, nearly hitting the water. Line hissed through my fingers and arched out into the lake across the crests of the growing waves. The fish had taken all of the slack and was on the reel as he powered out into the depths of the tormented lake. The reel screamed and I had applied as much pressure as I dared when the big brown jumped. He cleared the water and seemed to hang against the lowering sky for seconds before landing slab-sided in a trough between the waves.

A cheer erupted from behind me as the fish jumped a second time, and a third, and then a fourth. I had just begun to feel in control of the situation when the line went sickeningly slack. The crowd, now gathered at the water’s edge moaned collectively, like a mortally wounded beast. As my heart sank, the fished rocketed from the waves again… and again… and one last time! Everyone cheered, but this time for the fish. I bowed my head in defeat, like a tragic character in an apocalyptic opera.

The crowd called out their condolences and drifted back to the fire, inviting me to share some wine and tell them my story, but I couldn’t. I felt like someone who, after years of trying, had finally won the lottery, and then lost the winning ticket. It was too painful to relive so soon. I thought of Jorge and his big fish, and knew that he’d understand if I went back to the lake.

I moved down stream to the next station, focused my energies as best I could, and prayed for another chance. On my second cast, as the fly swung deeply in the center of the river, a good fish took and ran down stream, through a field of boulders and towards the depths of the Fools’ Pool. I got my rod tip high and threaded my way downstream to the lip of the big pool. The fish circled there, unsure if it should go further downstream or make a break, back upriver, for the safety of the lake. I empathized with it’s dilemma, and understood its choice to stay and bide its time. After all, there is a certain sense of safety in indecision; how many times had I done the same thing, I wondered?

I wore down the fish carefully and gradually, and her frantic efforts into the green depths of the pool grew less and less determined. Finally, after she’d already spent all of the energy necessary to escape, she tried to gain the safety of the lake. Again, I understood her situation, and felt insight into my own life through her struggle. Failing in her attempt to reach the lake, she decided on an escape downriver. As she turned and ran past me, I swung my rod low and left, and used her momentum to turn her as she neared the shore.

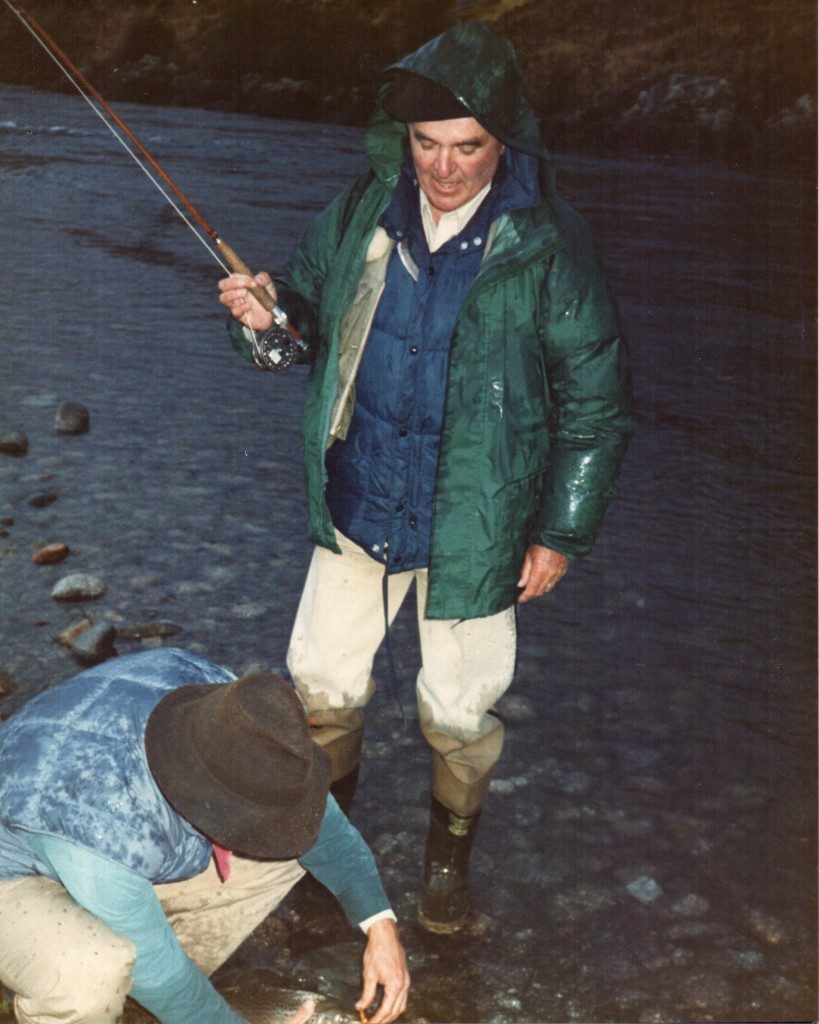

Defeated, she lay on her side, there in the shallow water, her eyes rolled down; focused on the world where she belonged. “Great fish!” said Prince Radziwill, as he grasped her through her gills and lifted her as a trophy for all to see. “Congratulations!”

“No!” I screamed, taking the fish back, and walking her out into the current. God damn it! I thought, as I watched a slight trace of blood pump through her gills. I knew from experience, that once a fish was bleeding from its gills, it was unlikely to survive after release.

I revived her as best I could, and let her slip from my hands. She swam upstream towards the lake and an uncertain future. “I’m so sorry,” I said, turning to the Prince. “I meant no offense. I was just taken with the moment. Please forgive my outburst.”

“I too understand,” he said. “The times have changed, and I think for the best. Please forgive me. I was also taken with the moment. Would you like some wine?”

But I didn’t stop and join the others after releasing the big brown. I stood on the lip of the “Fools Pool” and hooked a third big fish. I played it as best I could, determined to do everything right, but the big male threw the hook on its second jump and sulked in plain view until dark. Upon inspecting the fly, I found that I’d fractured the hook on a low back-cast. It was broken at the bend. But, there was still a point to it; the crowd, gathered there, before the river and at the edge of night, had cheered for the both of us.

A few days later, I sat on an airliner, and watched the sun set as I traveled north along the spine of the Andes. There was a lot to think about; much that I wanted to remember, and more that I was afraid to forget.

“There are many ghosts at the Boca.” Jorge had said, and I wondered about those ghosts. Were they the ghosts of fish or men? Weren’t the two really intertwined into one memory, and wasn’t that the essence of the ghost? If you fish hard and the fishing becomes your life, sooner or later you fish with ghosts; eventually you become one.

When I fish the Agulukpak Howard, Jacque, and my mentor, Jack are there with me.

Since that first season, I’ve lost many companions to the vagrancies of time. Jorge Donavan and Bebe have since crossed over; friends of mine report having seen them at the Boca.

I never wade the Malleo and not think of Florencia and now, my dear friend, Les.

I never fish the Kinnikinnic without remembering Ed.

Finn and Rupert still work the Upper Nushagak.

There are others; too many others.

These days, I rarely fish alone.

–

Post Script:

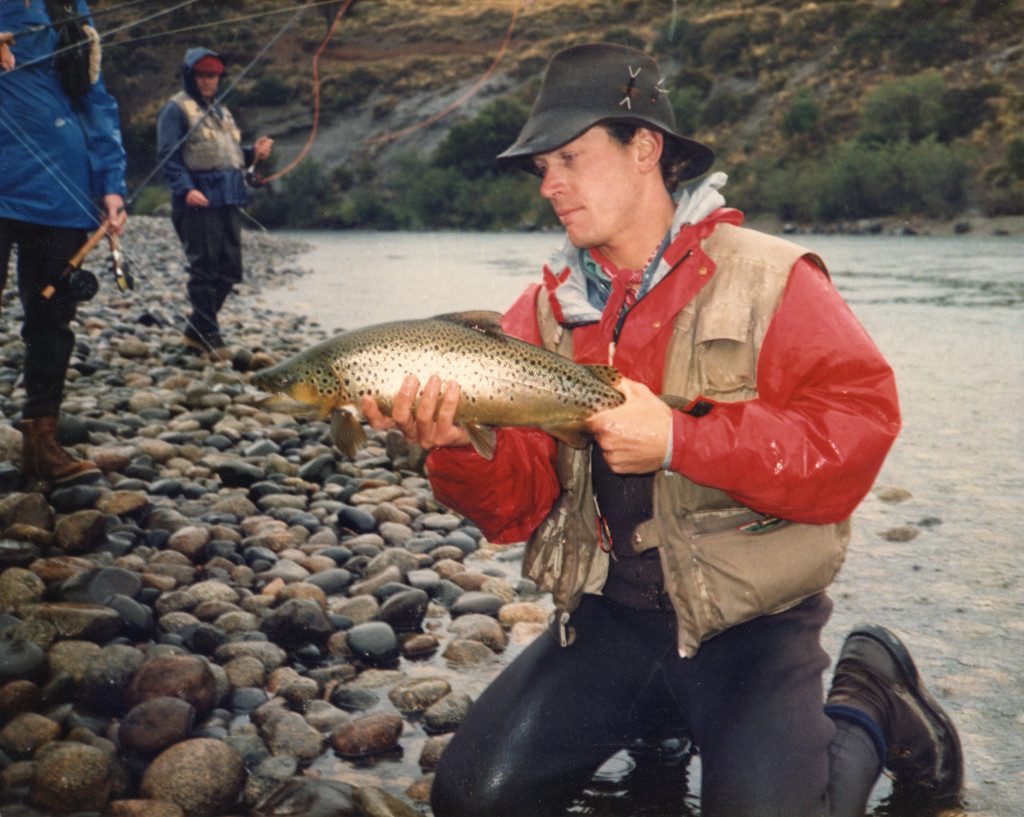

The day before I left Argentina, that first season, Jorge and I visited Bebe at his home on the Chimehuin. As we walked onto the grounds, we saw him standing by the river, playing a good fish. Bebe asked me to assist him in releasing it, and Jorge snapped a photo of the two of us in that moment. It hangs in the studio where I paint, and breaths life into my work.