“The creative mind plays with the objects it loves.” Carl Jung

My friends describe me as a collector, my wife calls me a pack rat, and my parents refer to me as obsessive. I suppose they’re all correct, and I don’t mind because I’ve been called much worse.

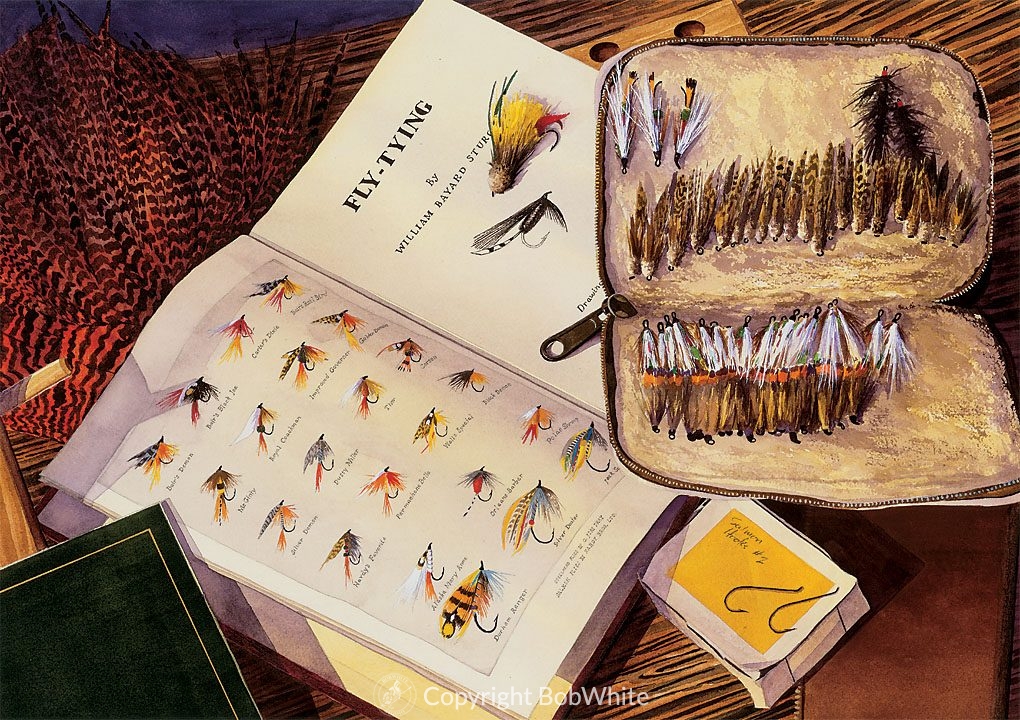

My fascination with flies started the moment I found my father’s old fly box in a dusty corner of the garage. There were a few cork popping bugs and all of the standard wet flies of the day; McGinty, Black Gnat, Royal Coachman, Yellow Sally, maybe even a Parmachene Belle or Red Ibis. They were pure magic to me, especially after my father told me that he had tied them himself.

Of course, the purpose of a fly is to catch fish, but after I’d sorted, organized, inventoried, and replaced them in their freshly cleaned box, the last thing in the world I intended to do was to lose a single one of them fishing. I was hooked on flies before I ever got one wet. Once I started sneaking onto the local farm ponds to poach panfish and the occasional bass, I developed a habit, which I still practice today; I never use my best flies unless I have to. When I’m selecting a fly I’ll pass over a particularly well-tied one and pick another that is fish worn but just good enough to work. Call it Germanic practicality, but I’d never consider using the last fly of a particular pattern or even the last of a size, lest I forget how effective it was and neglect to have an example to tie from in the future. There are certain flies that I wouldn’t think of leaving behind, and oddly enough, others I’d never consider fishing. These are usually flies from my childhood, or ones given to me by good friends or other noteworthy incorrigibles… my friends that guide.

My collection of flies is separated into three categories. I have large “inventory boxes” that hold an assortment of certain types of flies. Then, I have smaller “fishing boxes” that have a cross section of the inventory boxes, weighted with those that are particular favorites for the water I intend to fish. Finally, I have “archival boxes” that have an honored place on my bookshelves. These are flies that I would never fish for historic and sentimental reasons. With each passing season, the number of those in inventory shrinks and those on my book shelves swells.

If this seems like an excessive number of flies, consider the conversation that I had with my mortgage banker when I applied for my first home loan in the late 80’s.

“It’s a nice old home, Bob. Olga lived there for as long as anyone can remember, and she really took care of the place. I’m sure that you’ll love it. Now, how much do you need to borrow?”

I gave him a figure. “OK, that seems reasonable. What’s your annual income?”

I gave him a figure. “Oh… that might be a problem,” he said, getting down to business “What do you do for a living? Perhaps you have some property or equipment that would help you qualify.”

“I’m a fly fishing guide.” I replied. “I work in Alaska during the summer and in Argentina during the winter months.”

“Really! I’m a fly fisherman. Where in Alaska do you guide?” The conversation was pleasantly diverted for a few minutes while we discovered that we shared mutual friends and similar experiences.

“Well, you must have a few fly rods,” Mike asked, trying to be helpful.

I gave him a figure. “Good! We’ll average them out at, say $300 each. Reels and fly lines?”

I gave him the number. “Good, that’ll help. Do you have many flies?”

I gave him a conservative estimate. “Wow! Congratulations, you’ve just qualified for your loan.”

“How do you tie flies?” I once asked my father, as he admired the contents of the fly box that I’d just put into order. I never put anything away and my diligence had not gone unnoticed.

“I think my old fly tying stuff is around here somewhere,” he said wistfully.

Several fruitless hours later he emerged from the hot and dusty attic. “I guess it got thrown out,” he said. “Or, maybe I gave it away.”

The look of disappointment on my face must have been easily read because a week or so later a package with my name on it arrived from a company in Waseca, Minnesota. This was big stuff for a ten-year-old.

“Herters!” I whispered in awe as I ripped open the box. A fly tying kit! The old man had come through for me! I felt like the luckiest kid in the world that night as I sat down and attempted to tie my very first fly. The instruction manual gave me the basic concepts, but didn’t have any pattern recipes in it, so I copied the flies that my father had tied years before, not even knowing their names.

I sent catalog requests to every advertiser of fly fishing equipment I could find in all of the hunting and fishing magazines to which I was subscribed. Weeks later they began to arrive, and I knew that I’d hit the jackpot when the Orvis catalog fell open on my desk. Hundreds of different flies adorned page after page. The names were exciting and exotic; “Irresistible”, “Rat Faced McDougal”, “Hunt’s Teagle Bee”, “Silver Doctor”, “Bumble Puppy”, “Picket Pin”, “Mickey Finn”, “Cow Dung!”

I started tying with a vengeance. I was a child possessed. Though I’d never seen a trout, I instinctively knew that they were a more discerning judge of the fly tyers’ art than the bluegill and bass in my local water. I set a goal to have at least half a dozen of every trout fly in the Orvis catalog tied flawlessly by the time school started in the fall. Those that weren’t quite perfect became my “fishing” flies.

I gauged my world by the cost of fly tying materials. It took two lawn jobs to buy a gamecock neck. Washing and waxing the family car was worth a box of Mustad hooks. A Saturday spent cleaning the basement and garage might buy a good scissors and hackle pliers. If I was lucky and saved for a month, I might acquire that new Thompson “A” vise.

Things got really serious; I bought (and actually read) a book about fly tying. I had at least a thousand trout flies tied, and the dry flies pre-treated in silicone before I waded into that first trout stream. I’d like to say that things got better with time, but my wife and parents occasionally read these stories, and they’d call me on it. Let me just say that over the years, I’ve learned to feel rich when I have lots of flies, wool socks, shotgun shells and decoys.

Flies became an integral part of my life when I began to guide, and that obsession has lead to a few interesting experiences.

“Bawb, that was a smashing day’s sport!” Lady Rowcliffe said, as she lifted a glass of Malbec in my direction. “I must say, those little nymphs of yours are quite tony! I’m off to Bhutan from here to fish for Mahseer, a rather huge carp-like fish that lives in the most beautiful of rivers. I haven’t been able to take the beasties on a fly with any consistency. I don’t suppose that you have any suggestions?”

“Well, what do these beasties eat?” I asked, spreading a bit of butter and blue cheese on a crostini.

“On my last trip, I’d awake early each morning to write my letters, have a spot of tea, and watch the monkeys. The filthy little buggers take their morning crap right into the river.”

That’s what I love about Lilla; she’s as comfortable talking about a monkey’s morning ritual as the variety of roses that surround her family estate. “Well,” she continued. “As the dirty little blighters shat from the bana tree, the mahseer rose to their little turds!”

“No shit?” Heads in the dining room turned our way.

“Precisely.”

“Lilla, what you need is a “Monkey Shit” fly!” I exclaimed a bit too loudly. “Do the turds float for long?”

“Quite right, for just a bit.”

“I know exactly what you need!” I explained as we dove into the second course, and a bit more red wine.

I tied several versions of the Monkey Shit fly the next day while Lilla slept siesta. Essentially, it was a simple spun and clipped deer hair pattern, nothing more than the head of a muddler minnow on a short shank hook. I fussed with different variations trying to make it more interesting, but you can only do so much with a piece of monkey shit.

Months later, Lilla wrote to inform me that she had indeed caught a record Mahseer using one of my monkey shit flies. I tucked the letter and photos inside of a copy of a book that mentions the episode, “Salmon & Women”, by Wilma Paterson.

Years before, I was on the south branch of the AuSable River with my friends Dan and Fred. It was the middle of June, and we were there for the Hex hatch, or “Michigan Caddis” as the locals referred to them. It was still too early for the after-dark hatch of the big mayflies, but we’d just arrived and were anxious to fish. It was settled when Fred mentioned that the evening before he’d seen some caddis activity just upstream from the camp.

“It was the damnest thing,” he said. “Yesterday evening the river was on fire. I mean the water was boiling with good fish. Then it just stopped; as if someone had thrown a switch!”

While caddis hatches are notoriously difficult, this was particularly unusual, and it was just the excuse we needed to get on the river early. We reached the stretch of water that Fred had fished the evening before and sat down to wait for the hatch. True to his word, the fish started feeding. Small fish at first, taking the emerging flies in splashy leaps that took them cleanly out of the water. The momentum built until the air was swarming with rolling clouds of swirling flies and the river was alive with trout.

We spread out and each took claim to a bit of river; one wouldn’t need much, and started looking for the larger fish. Fred was the first to hook-up; I suspect because he’d scouted out a particular fish the night before. Dan was soon into a good one, and I’d missed a couple when the feeding abruptly stopped. Fred arched an eyebrow, shrugged his shoulders, and did a horrible Bugs Bunny imitation.

“Dat-dat-dat-dat’s all folks.”

“Well, I’ll be,” Dan said. “Hey, listen, what’s that?”

Somewhere up stream we heard a soft birdlike voice cooing and giggling. We reeled up and pushed through the alders following the laughter. “It sounds like it’s coming from the old Truettner place,” Dan whispered.

We eased our way to the river’s edge and watched as the old woman reached into a huge basket of bread, and tossed crumbs to the fish waiting below her bridge. The water seethed with hundreds of trout.

“Every fish for half a mile must be here.” Fred murmured.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” Dan said.

“I’ve got an idea.” I whispered, as we turned to leave.

I’d camped my way across Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to get to Grayling, and had slept on a closed-cell foam pad. It was a simple matter to cut off a few chunks and lash them to a hook. “Instant bread fly.” I announced when the whip-finish was complete.

A plan was hatched at breakfast the next day. The river was public; we could legally fish wherever we wanted, though Dan thought it in bad form to fish directly below the bridge. Old Mrs. Truettner was a neighbor, and he didn’t want to upset her. We’d keep our distance and pick up what we could from the fringes.

We were waiting the next evening when the old woman appeared, as if by magic, in the gloaming. “Time to eat, my little pets,” she cackled, throwing a single breadcrumb into the water. It drifted only a few feet before disappearing in a swirl that would get any fly fisherman’s attention. The crumbs came quicker and the fish responded as if to a dinner bell. We began casting our manna upon the water and the motion caught the old ladies attention. She squinted and strained to make out who it was in the gathering darkness.

“Who’s out there!” she croaked. “Leave my pets alone!”

But, there was really no reason for her concern. Every fish for six bends down river was directly below her bridge feasting on Wonderbread.

I just couldn’t help myself; I stripped out the necessary line and threw it all, straight up river to within a few yards of the bridge. It wasn’t as close as I’d wanted it to be, but it was close enough. The strike was instantaneous and my rod bent double to the weight of a good fish. “Scoundrels!” She hissed.

The fish jumped and landed slab-sided on the water. “Villains!” She spit. “I’ll fix you!” She dumped the entire basket into the river in a shower of crumbs. The fish went wild in a frenzy that frothed the water. But, as desperate as they were to consume every last morsel, they simply couldn’t eat it fast enough. The bread and the feeding fish started to drift away from the bridge and directly past us. For fifteen minutes we enjoyed some of the best fishing that has ever been had on the South Branch.

When we returned to the cabin, Dan’s father, Phil was sitting on the porch over looking the river, smoking his pipe and sharing a bottle of bourbon with the Crawford County sheriff. “You fellas wouldn’t know anything about some villainous criminals bothering an old woman would you?” He asked.

“Why no, Tom. What’s happened?” Dan asked innocently.

“Oh, nothing really. Nothing that I haven’t wanted to do myself for almost ten years now.”

Years later on the Agulukpak River in Alaska, I was cleaning up after a shore lunch, and watched a piece of cornbread disappear into an all too familiar swirl. “I’ve got an idea.” I whispered…

—

Post Script:

Perhaps I sensed the path down which those little pieces of thread, feathers, and floss in my father’s old fly boxes would take me… to Alaska and then to Patagonia, with lots of stops in between. Maybe I sensed that there was an entire subculture of fly fishing out there waiting to be embraced. Most probably, I was just an obsessed little kid. Some things never change.

Yes, there is a copy of the Monkey Shit fly in the archive box.